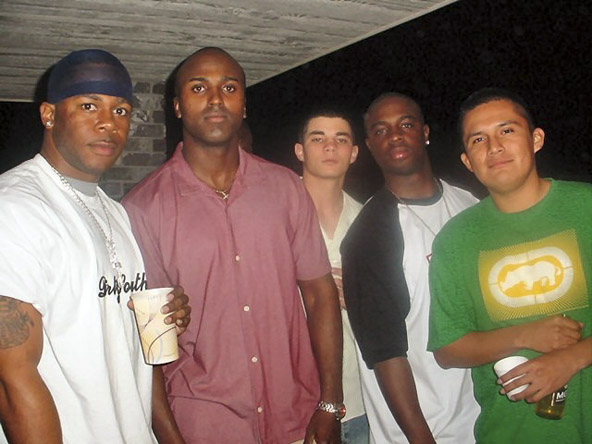

Sergeant First Class Reggie Butler, First Cavalry Divsion, with Ahmed Cason and friends.

Photo: unknown

Reggie Butler led his platoon on the relief mission for the Charlie Company convoy trapped in the city-wide ambush on April 4. He went out twice that day, trying to rescue trapped soldiers. The cadences and rhythms in his voice are Southern -- he does not have any of the nervous intensity of men from cities; he is measured and clear. Butler is also honest and soft-spoken, a quality that draws the other soldiers to him. Only 30, he has been married twice and speaks Albanian, which he picked up on his peacekeeping mission in the Balkans. Butler's wife is German and she is in Europe with his daughters, waiting for him to return.

In his room at the base in Sadr City, as Butler began telling me the story of what happened on April 4 he was calm and even. But once he got going, he talked without pausing for two hours. His account of April 4 reminded me of torture victims curing themselves though speech, a deliberate purging of events from his mind. Stories poured out of him. The most wrenching part of Butler's experience was the death of his close

friend, Spc. Ahmed Cason, who was shot as he stood in the Humvee gunner's well a few inches away. Butler, along with the other members of the platoon, had taken several turns, heading deeper into the city where the fighting intensified, driving into what would quickly become a citywide ambush. When he described how much shooting was coming down from the rooftops, Butler pantomimed rain.

"Some guys were frozen, scared, they were gone, they were just lost. That's when Cason was hit. After he got hit, he dropped down, then he got back up and started shooting. I didn't think he was hurt that bad. Then he dropped down and he was bleeding all over the Humvee. Crabbe, the medic, started pulling off his clothes, doing first aid. I asked how he was doing and Crabbe told me, 'We need to get him out right now.'" The entire city was firing from the buildings on the broad avenues. One Alpha Company gunner told me, "You could see the battlefield just opening out in front of your eyes. It was amazing," and he shook his head in disbelief.

After Cason was shot, Butler and his team spent the next 15 minutes being ambushed and unable to move. While they struggled to get out, Cason was bleeding to death. "Cason came to me and asked to be in my crew in Iraq; he said, 'If we go to Iraq I want to be in your vehicle.' So I made it happen," Butler said. He was working on a slide show for Cason when I walked into his room to talk about April 4.

Butler wrote a powerful and simple eulogy that was read at the fallen-soldier ceremony for Cason. Butler's computer is full of pictures he's taken during the war. There is a snapshot of Cason drinking beer; there are pictures of Cason's fallen-soldier ceremony. After knocking on Butler's door, I realized I had stumbled into a memorial in progress. Butler was sitting on his bed talking, surrounded by cards from home, the archivist and conscience of the platoon.

As he described the route his Humvee took through the roadblocks that day, he did not exaggerate or use the saccharine rhetoric of liberation; he described events in concrete terms. There is a straightforward reason for this -- Butler is trying hard, along with the other members of Alpha Company, merely to live through Sadr City.

He has a long way to go.

As it has with many other frontline soldiers serving in Iraq, the military has "stop- lossed" Butler, which means that he is not allowed to leave the Army until the Iraq deployment is over and his unit is replaced 10 months from now. If the cease-fire with the al-Mahdi Army breaks down, the odds that he will make it through without serious injury spike sharply downward. Worse yet, senior officers at Camp Eagle have been leaning on him to reenlist. "You know, they tried to really guilt-trip me, saying, 'The military has spent a lot of money training you.'"

In the abstract universe of military balance sheets, this is true -- Butler explained he is one of only six sergeants of his rank who has graduated from the elite Ranger school and is also qualified as a master gunner. But after going out on missions with him, I began to understand that the real reason the commander wants to keep him is that the 1st Platoon might not survive his departure. It is Reggie Butler's indispensability that makes him so dispensable. Catch-22.

On June 27, four days into my stay on the base, Butler was coming out of the command post for Alpha Company just as I was going in. He asked me if I was going out in the

afternoon. I said yes, I was joining a mission to the Sadr City power substation to ask the engineers what they needed in way of supplies. "Well, if you get into anything, I'm the one coming out for you," Butler said.

After leaving the substation, the Bradleys threw comet trails of dust down the street and then stopped to perform a snap checkpoint, which involves choking off the traffic in both directions, while Iraqi soldiers searched cars full of young men. As soon as the Bradleys pulled up on the wide median, a crowd gathered on each side of the road to watch the Americans. When the Iraqi soldiers went over to perform crowd control, the young men on the street started to jeer and taunt them, calling the Iraqi soldiers traitors and collaborators.

I watched one young Iraqi soldier named Hosham stand in front of 50 jeering residents, shouting back at them because he couldn't take their insults. The boys in the crowd started singing the al-Mahdi Army song in which they pledge to spill their blood for Moqtada. When Hosham finally pulled the bolt back on his Kalashnikov, the crowd only found worse taunts. Hosham stood in front of the gawkers, held his rifle in the air, pulled the trigger and fired a burst that echoed off the houses. Everything changed. The sidewalk crowd fell silent, then drew back and became an angry mob. The vendors selling gasoline on the sidewalk raised their fists and neighborhood men started to come out of their houses. The crowd grew.

Sergeant Reggie Butler's determination to keep his men safe made him a hero of this story, there's no other word for it. After the piece ran, I received sharp criticism from senior officers but I believe it stands on its own.

No One is Going Through What We Are Going Through was originally published in Salon.com.

LEAD IMAGE: 7 August, 2007, Baghdad, Iraq. Mahdi Army militiamen on patrol in a sector of the city shared by the First Cavalry Division. These men were involved in numerous actions against U.S. forces until a rickety ceasefire took effect. The ceasefire collapsed in late August and the militias under Moqtada al Sadr resumed fighting. Reggie Butler and his unit faced these men over a period of months.

LEAD IMAGE: 7 August, 2007, Baghdad, Iraq. Mahdi Army militiamen on patrol in a sector of the city shared by the First Cavalry Division. These men were involved in numerous actions against U.S. forces until a rickety ceasefire took effect. The ceasefire collapsed in late August and the militias under Moqtada al Sadr resumed fighting. Reggie Butler and his unit faced these men over a period of months.Video Still: Andrew Berends/Storyteller Productions

© Phillip Robertson, 2009-2014.