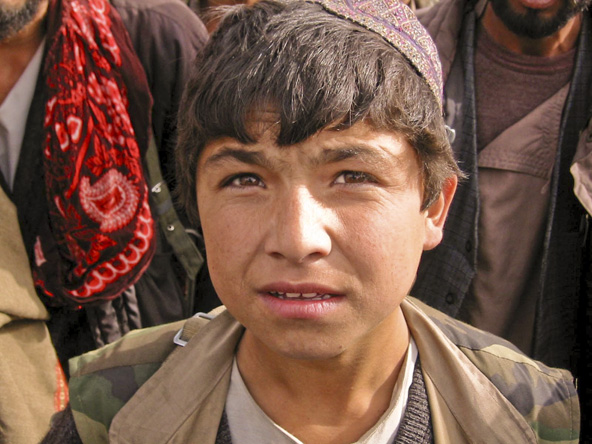

4 November, 2001, Afghanistan. A child fighter with Northern Alliance forces as they prepare to take the city of Taloqan.

Photo: Phillip Robertson

Feb. 4, 2002 Kabul-Kandahar Road | Afghanistan

Most Westerners instead chose the absurdly long route through Pakistan, which meant flying to Islamabad on a U.N. plane, flying south to Quetta, and then tunneling back into Afghanistan at a place called Spin Boldak. A multinational detour, complete with high bribes and visa hassles, just to avoid the Kabul to Kandahar shakes. But if you didn't have the money or the time to do the Pakistani route, driving started to look like a real option.

The word was that the road was full of bandits, part of an ever-worsening security situation following the end of the war. Of course, ordinary Afghans trying to visit relatives in another province can't take the U.N. flights, so they take their chances. It's a trip that takes about two days if nothing goes wrong. Coming from Kabul, most travelers stay the night in a town called Ghazni, about 150 kilometers from the capital, then get up before dawn and drive the rest of the way to Kandahar, another 400 kilometers. The road, a southwestern arc that crosses Wardak, Ghazni, Zabul, and Kandahar provinces, also crosses cultures and tribes. People in each province wear signature clothing, turbans and caps of certain colors, and speak slight variations of Pashto. Moving south, turbans take the place of pakuls, the woolen hats worn by the mujahedin, and the cloth of choice gets darker. Kandaharis wear black turbans. We decided to leave Kabul on Friday, Jan. 25, after we learned that the blind lion at the Kabul Zoo had died.

Kabul had become dry and sleepy. Kofi Annan's visit snarled traffic for a whole day. At one point the big news was that a British Gurkha regiment had arrived to join the peacekeeping force. In the Mustafa Hotel, one TV crew was so hard up for a story they interviewed the owner, a new low. Kandahar was promising, and Aman Khan, my translator, said he could get us there if that was what I really wanted. But our driver, Abdullah, did not want to go to Kandahar. Abdullah was from Jalalabad in Nangarhar province, and it was too far for him, too distant from his own people. Asking him to drive all the way across the country was like asking him to become an astronaut or a Russian test pilot. I wheedled, bullied, then begged him to pull his minivan together so we could go. He ultimately gave in, but still didn't want to do it. We packed on Saturday night, and prepared to leave at 7 the next morning for Ghazni.

A few days before, in the bird market, I'd found two canaries for the room in the Mustafa. They lived in a Chinese wire cage and fought all the time. Walikh, a kid who was always hanging around our floor, kept stopping by with presents for them. Boiled egg, bits of bread. The bird market gangsters had kept them outside in the cold,and the gray canary was weak, but Walikh brought him back with all the attention. We took them down to the car on Sunday morning with everything else.

It was bright and cold as we drove out to the gates of the city, which were two shipping containers standing on end. We cleared the checkpoint after an argument with the militia. On our way out of town, listening to the Persian singer Nagma on the tape deck, we drove through the destroyed suburbs, a monument to the unrestrained bloodletting of 1993 in which 10,000 civilians were killed as Gulbuddin Hikmetyar attacked the Rabbani government. Only a year later, Hikmetyar and Rashid Dostum, the Uzbek warlord from Mazar-e-Sharif, fought for control of Kabul, destroying even larger sections of the city. We drove through miles of ruins. Since then, Dostum, a man known for his brutality and shifting allegiances, has become deputy defense minister in the Karzai government, leaving many people with a sense of foreboding for the Afghan government. At Sur Pol we crossed the Kabul River, a bright silver band. Pointing to the hills and ridges, Aman said, "Do you see those mountains? They are not rock, they are made of dust."

There were deep washes and gullies that marked the boundaries of a much larger river, but the water had retreated underground. The drought-ridden land looked like it had been scoured of anything green, and I wondered how the citizens of the villages hung on, living so far up in the mountains without water or fuel. Fifty kilometers outside Kabul the paved road ended and the van bounced along in the ruts, Abdullah swerving to stay out of the path of trucks. The canaries fluttered and chirped in the back seat.

For security, we had brought a Chinese automatic from Nangarhar province. We wrapped it in three plastic bags and hid it under the jack and a few greasy tools. The gun was strictly a last-chance deal, and we never referred to it by name, always saying, "Is that thing loaded?" or "Do you have that thing?" The gun lived under the front seat and we tried not to think bad thoughts. The way to Ghazni was peaceful, the villages relaxed and we were there by 12:30, feeling good.

Ghazni is one part ancient city and one part truck stop. On my map, Ghazni had a "Historical Scientific Center, Walled Picturesque City" annotation, next to a small star. The city contains the artifacts of three civilizations: Buddhist, Medieval Muslim. Near the road, there was a brisk car repair business where mechanics in oily shalwars swapped out axles that had been destroyed by the rutted highway, and any other car part that needed fixing. Welders worked from generator power. Convoys of trucks pulled in and stayed the night, leaving their engines running. We checked into the trucker hotel, the Spinzar.

LEAD IMAGE: 4 November, 2001, Afghanistan. A rocket bearer with Northern Alliance forces. Many male children without a means of support are picked up by fighters who give them food and shelter. I believe that a great number of these children are abused by the older men in their units. None of these children could read or write.

LEAD IMAGE: 4 November, 2001, Afghanistan. A rocket bearer with Northern Alliance forces. Many male children without a means of support are picked up by fighters who give them food and shelter. I believe that a great number of these children are abused by the older men in their units. None of these children could read or write.Photo: Phillip Robertson.

To contribute or commission a new Afghanistan assignment, click here.

© Phillip Robertson, 2009-2014.